Theories About Atlantis

PLATOIt was for Greek philosopher to bring to the world the story of the lost continent of Atlantis.

His story began to unfold for him around 355 B.C. He wrote about this land called Atlantis in two of his dialogues, Timaeus and Critias,around 370 B.C. Plato said that the continent lay in the Atlantic Ocean near the Straits of Gibraltar until its destruction 10,000 years previous.

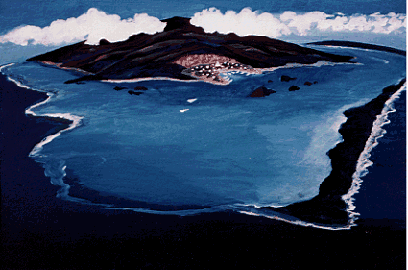

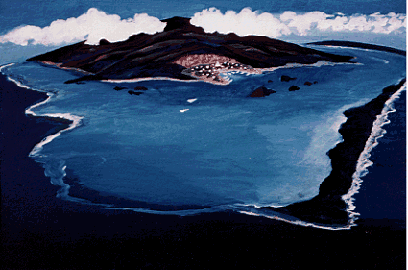

The Capitol of Atlantis The Capitol of Atlantis

Plato described Atlantis as alternating rings of sea and land, with a palace in the center 'bull's eye'.Plato used a series of dialogues to express his ideas. In this type of writing, the author's thoughts are explored in a series of arguments and debates between various characters in the story.

A character named Kritias tells an account of Atlantis that has been in his family for generations. According the character the story was originally told to his ancestor Solon, by a priest during Solon's visit to Egypt.

According to the dialogues, there had been a powerful empire located to the west of the "Pillars of Hercules" (what we now call the Straight of Gibraltar) on an island in the Atlantic Ocean. The nation there had been established by Poseidon, the God of the Sea. Poseidon fathered five sets of twins on the island. The firstborn, Atlas, had the continent and the surrounding ocean named for him. Poseidon divided the land into ten sections, each to be ruled by a son, or his heirs.

The capital city of Atlantis was a marvel of architecture and engineering. The city was composed of a series of concentric walls and canals. At the very center was a hill, and on top of the hill a temple to Poseidon. Inside was a gold statue of the God of the Sea showing him driving six winged horses.

About 9000 years before the time of Plato, after the people of Atlantis became corrupt and greedy, the Gods decided to destroy them. A violent earthquake shook the land, giant waves rolled over the shores, and the island sank into the sea never to be seen again.At numerous points in the dialogues Plato's characters refer to the story of Atlantis as "genuine history" and it being within "the realm of fact." Plato also seems to put into the story a lot of detail about Atlantis that would be unnecessary if he had intended to use it only as a literary device.

In "Timaeus," Plato described Atlantis as a prosperous nation out to expand its domain: "Now in this island of Atlantis there was a great and wonderful empire which had rule over the whole island and several others, and over parts of the continent," he wrote, "and, furthermore, the men of Atlantis had subjected the parts of Libya within the columns of Heracles as far as Egypt, and of Europe as far as Tyrrhenia."

Plato goes on to tell how the Atlanteans made a grave mistake by seeking to conquer Greece. They could not withstand the Greeks' military might, and following their defeat, a natural disaster sealed their fate. "Timaeus" continues: "But afterwards there occurred violent earthquakes and floods; and in a single day and night of misfortune all your warlike men in a body sank into the earth, and the island of Atlantis in like manner disappeared in the depths of the sea."Interestingly, Plato tells a more metaphysical version of the Atlantis story in "Critias." There he describes the lost continent as the kingdom of Poseidon, the god of the sea. This Atlantis was a noble, sophisticated society that reigned in peace for centuries, until its people became complacent and greedy. Angered by their fall from grace, Zeus chose to punish them by destroying Atlantis.By Plato's account, Poseidon, god of the sea, sired five pairs of male twins with mortal women. Poseidon appointed the eldest of these sons, Atlas the Titan, ruler of his beautiful island domain. Atlas became the personification of the mountains or pillars that held up the sky. Plato described Atlantis as a vast island-continent west of the Mediterranean, surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean. The Greek word Atlantis means the island of Atlas, just as the word Atlantic means the ocean of Atlas.

Atlas Atlas

By Egyptian record, Keftiu was destroyed by the seas in an apocalypse. It seems likely Solon carried legends of Keftiu to Greece, where he passed it to his son and grandson.

Plato recorded and embellished the story from Solon's grandson Critias the Younger. As in many ancient writings, history and myth were indistinguishably intermixed. Plato probably translated "the land of the pillars which held the sky" (Keftiu) into the land of the titan Atlas (who held the sky). Comparison of ancient Egyptian records of Keftiu identifies a number of similarities to Plato's Atlantis. It seems likely that Plato's Atlantis was a retelling (and renaming) of Egypt's Keftiu.

When Plato identified the location of the land he named Atlantis, he placed it to the west-in the Atlantic Ocean. In reality, Egyptian legend placed Keftiu west of Egypt, not necessarily west of the Mediterranean. In describing Atlantis as an island (or continent) in the Atlantic Ocean, we suspect Plato was merely wrong in his interpretation of the Egyptian legend he was retelling.

Yet Plato preserved enough detail about the land of Atlantis that its identification now seems very likely, and rather less mysterious than many new-age advocates would like. It is likely that Atlantis was the land of the Minoan culture, namely ancient Crete and Thera. If this hypothesis is correct, Plato never realized that the land of Atlantis was already familiar to him. Let's have a look at the evidence which suggests that Minoan Crete and surrounding islands bear a striking resemblance to what Plato described as Atlantis.

Archaeological records show that the Minoan culture spread its dominion throughout the nearby islands of the Aegean, very roughly from 3000 years BC to about 1400 years BC. Crete, now part of Greece, was the capital for the Minoan people an advanced civilization with language, commercial shipping, complex architecture, ritual and games.

It seems very likely that related islands (e.g. Santorini/Thera) may have been part of the same culture. The Minoans were peaceful: very little evidence of military activity was found in their ruins. A 4-storied palace at Knossos, Crete, was said to be the capitol of the Minoan culture. Correspondence of Minoan cultural artifacts with aspects of the Atlantis legend make the identity of the two seem virtually certain. Perhaps the most unusual of these is the Minoan bull fighting.

By Egyptian legend, the inhabitants of Keftiu would engage in ritualistic bull fighting, with unarmed Minoan bullfighters wrestling and jumping over uninjured bulls.

This same foolhardy practice is richly illustrated in remaining Minoan artwork.Plato's (Egyptian) legend also holds that Atlantis was peaceful - this is confirmed by a virtually complete absence of weapons in Minoan ruins and in Minoan artwork - unusual for peoples of that time. Egyptian legend held that elephants were found on Keftiu - while there were presumably no elephants on Crete, the Minoans were known to deal in African ivory, and appear to have been the principal access to ivory for Egypt 20 centuries before Christ.

Plato's maps of Atlantis have even been argued to resemble the geography of ancient Crete.

Many ancient Greek myths take their location from Minoan Crete more than ten centuries before Plato. Daedalus, the ancient scientist, was supposedly the architect of the palace at Knossos.

There one can still find ruins alleged to be the labyrinth that housed the legendary Minotaur, the monster (half-human, half bull) haven been slain by Thesius.

So ancient myths were not new to Minoan Crete. Regardless of the legend, Minoan culture extended across the island of Crete, with most of its developments along the northern coast of Crete. But, after more than a thousand years of dominance, the Minoan culture came to an abrupt end, circa 1470 BC.

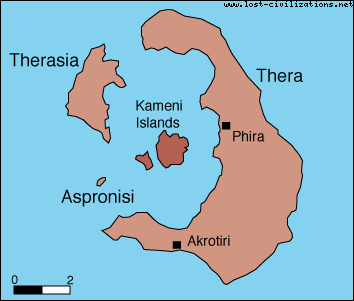

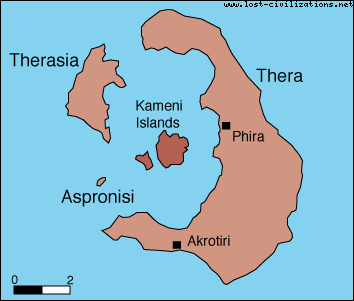

But what of the fabled apocalypse which, according to the Egyptians, swallowed Keftiu-Atlantis in one day and one night? This also has basis in historical fact. The trail of evidence leads to the small island of Santorini.

Santorini (also known as Thera) lies 75 km north of Crete. Santorini (also known as Thera) lies 75 km north of Crete.Santorini was also a Minoan land, and ruins can be found throughout the island. A mountain lay at its center, probably about 1500 meters in height until approximately 1500 BC. This mountain was a volcano; eruptions began about 1500 BC, and smoldered until a final climax about 1470 BC. Geologically, not all volcanoes are the same.

Some drip lava slowly for centuries, others explode cataclysmically. From tectonic location, composition, and physical structure one can identify similarities between volcanoes. The volcano at Santorini was geologically similar to the 19th century Pacific volcano Krakatoa, and quite different from (for example) the volcanoes on Hawaii. Krakatoa exploded violently in 1883, spreading unparalleled tidal waves (tsunamis) throughout the southwest pacific, and filling the atmosphere with ash that spread through the entire world.

Santorini was about 4 times larger than Krakatoa, and probably at least twice as violent. The fury of Santorini's final explosion is inferred from geologic core samples, from comparison to the detailed observations made on Krakotoa in 1883, and from the simultaneous obliteration of almost all Minoan settlements. The geologic record dates the final explosion of Santorini with remarkable accuracy. The likely picture then, is this.

In summer, circa 1470 BC, Santorini exploded. Volcanic ash filled the sky, blotted out the sun, and triggered hail and lightning. A heavy layer of volcanic ash rained down over the Aegean, covering islands and crops. Earthquakes shook the land, and stone structures fell from the motion. When the enormous magma chamber at Santorini finally collapsed to form the existing caldera, enormous tsunamis (tidal waves) spread outward in all directions.

The coastal villages of Crete were flooded and destroyed. The only major Minoan structure surviving the waves and earthquakes was the palace at Knossos, far enough inland to escape the tidal waves. But in the days that followed, volcanic ash covered some settlements, and defoliated the island.

In famine from the ash, with the bulk of their civilization washed away, the remaining Minoans were overrun by Mycaeneans from Greece, and Knossos finally fell.

The modern island of Santorini is now the rim of the volcano - the caldera is covered by the Aegean Sea. Mounds of pumice and volcanic ash mark its center, where the volcano remains. New inhabitants of Santorini mine the volcanic ash to make cement - and still find ancient ruins under the stone. The ash is now the soil, olive and fruit trees cover the landscape, and former Atlantis (Crete, Santorini, and perhaps other Aegean islands) is mostly buried. New inhabitants have rebuilt Crete, but the mute ruins of ancient Atlantis can still be seen.

The End of Atlantis: New Light on an Old Legend

Atlantis was governed in peace, was rich in commerce, was advanced in knowledge, and held dominion over the surrounding islands and continents. By Plato's legend, the people of Atlantis became complacent and their leaders arrogant; in punishment the Gods destroyed Atlantis, flooding it and submerging the island in one day and night. Although Plato was the first to use the term "Atlantis," there are antecedents to the legend. There is an Egyptian legend which Solon probably heard while traveling in Egypt, and was passed down to Plato years later. The island nation of Keftiu, home of one of the four pillars that held up the sky, was said to be a glorious advanced civilization which was destroyed and sank beneath the ocean.More significantly, there is another Atlantis-like story that was closer to Plato's world, in terms of time and geography... and it is based in fact. The Minoan Civilization was a great and peaceful culture based on the island of Crete, which reigned as long ago as 2200 B.C. The Minoan island of Santorini, later known as Thera, was home to a huge volcano. In 1470 B.C., it erupted with a force estimated to be greater than Krakatoa, obliterating everything on Santorini's surface. The resulting earthquakes and tsunamis devastated the rest of the Minoan Civilization, whose remnants were easily conquered by Greek forces.

And there exists yet another strong possibility: that Plato entirely made Atlantis up himself.Regardless, his story of the sunken continent went on to captivate the generations that followed. Other Greek thinkers, such as Aristotle and Pliny, disputed the existence of Atlantis, while Plutarch and Herodotus wrote of it as historical fact. Atlantis became entrenched in folklore all around the world, charted on ocean maps and sought by explorers.In 1882, Ignatius Donnelly, a U.S. congressman from Minnesota, brought the legend into the American consciousness with his book, Atlantis: The Antediluvian World.

Edgar Cayce(1877-1945) became the U.S.'s most prominent advocate of a factual Atlantis. Widely known as The Sleeping Prophet, Cayce claimed the ability to see the future and to communicate with long-dead spirits from the past. He identified hundreds of people -- including himself -- as reincarnated Atlanteans.Cayce said that Atlantis had been situated near the Bermuda island of Bimini. He believed that Atlanteans possessed remarkable technologies, including supremely powerful "fire-crystals" which they harnessed for energy. A disaster in which the fire-crystals went out of control was responsible for Atlantis's sinking, he said, in what sounds very much like a cautionary fable on the dangers of nuclear power. Remaining active beneath the ocean waves, damaged fire-crystals send out energy fields that interfere with passing ships and aircraft -- which is how Cayce accounted for the Bermuda Triangle.Cayce prophesied that part of Atlantis would rise again to the surface in "1968 or 1969." It didn't, and no one has yet found hard evidence that it was ever there. With sonar tracing and modern knowledge of plate tectonics, it appears impossible that a mid-Atlantic continent could have once existed. Still, many argue that there must have been an Atlantis, because of the many cultural similarities on either side of the ocean which could not have developed independently, making Atlantis quite literally a "missing link" -- the topographical equivalent of Bigfoot.In more ways than one.

Perhaps Santorini was the "real" Atlantis. Some have argued against this idea, noting Plato specified that Atlantis sank 10,000 years ago, but the Minoan disaster had taken place only 1,000 years earlier. Still, it could be that translation errors over the centuries altered what Plato really wrote, or maybe he was intentionally blurring the historical facts to suit his purposes.

And there exists yet another strong possibility: that Plato entirely made Atlantis up himself.Regardless, his story of the sunken continent went on to captivate the generations that followed. Other Greek thinkers, such as Aristotle and Pliny, disputed the existence of Atlantis, while Plutarch and Herodotus wrote of it as historical fact. Atlantis became entrenched in folklore all around the world, charted on ocean maps and sought by explorers.In 1882, Ignatius Donnelly, a U.S. congressman from Minnesota, brought the legend into the American consciousness with his book, Atlantis: The Antediluvian World.

Edgar Cayce(1877-1945) became the U.S.'s most prominent advocate of a factual Atlantis. Widely known as The Sleeping Prophet, Cayce claimed the ability to see the future and to communicate with long-dead spirits from the past. He identified hundreds of people -- including himself -- as reincarnated Atlanteans.Cayce said that Atlantis had been situated near the Bermuda island of Bimini. He believed that Atlanteans possessed remarkable technologies, including supremely powerful "fire-crystals" which they harnessed for energy. A disaster in which the fire-crystals went out of control was responsible for Atlantis's sinking, he said, in what sounds very much like a cautionary fable on the dangers of nuclear power. Remaining active beneath the ocean waves, damaged fire-crystals send out energy fields that interfere with passing ships and aircraft -- which is how Cayce accounted for the Bermuda Triangle.Cayce prophesied that part of Atlantis would rise again to the surface in "1968 or 1969." It didn't, and no one has yet found hard evidence that it was ever there. With sonar tracing and modern knowledge of plate tectonics, it appears impossible that a mid-Atlantic continent could have once existed. Still, many argue that there must have been an Atlantis, because of the many cultural similarities on either side of the ocean which could not have developed independently, making Atlantis quite literally a "missing link" -- the topographical equivalent of Bigfoot.In more ways than one.

|

|

The Capitol of Atlantis

The Capitol of Atlantis

Atlas

Atlas

Santorini (also known as Thera) lies 75 km north of Crete.

Santorini (also known as Thera) lies 75 km north of Crete.