http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2012/07/18/mitt-romney-polls_n_1680827.html

Likely Voter Polls: Mitt Romney's Hidden Edge?

Posted: 07/18/2012 8:46 am Updated: 07/18/2012 9:20 am

WASHINGTON

Are national media and pollsters oversampling Democrats? That's a charge made by some pundits, and they may have a point:

If the most recent polls could accurately predict which self-identified registered voters actually would cast ballots in November, their horse race numbers on the presidential election likely would tip a few points more Republican.

Nevertheless, pollsters generally are reluctant to impose their educated guesses about voter turnout on their results at this stage of the race. That hesitation, and the reasons for it, reveal important details about the assumptions pollsters make and about the limitations of horse race polls generally.

Consider the criticism leveled at the Pew Research Center poll released last week that showed President Barack Obama leading presumptive Republican nominee Mitt Romney by a seven-point margin (50 to 43 percent) among 2,373 registered voters.

Some conservative pundits attacked the survey for a sample they said included too many Democrats. A correspondent quoted by National Review contributor Jim Geraghty took the critique a step further, claiming that "every" final pre-election poll conducted by Pew Research since 1992 "appears to lean to one direction -- always toward the Democrat, and by an average of more than 5 percentage points."

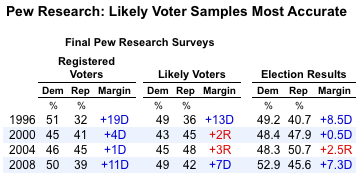

The biggest flaw in that argument is that it focuses only on results among registered voters released by Pew Research and overlooks Pew's final poll results released since 1996 among respondents deemed most likely to vote. In those four presidential elections, the Pew Research likely voter subgroup has been both more Republican in its composition than the registered voter sample, and a generally accurate forecast of the eventual result.

The consistent difference between the registered and likely voter samples raises the question: If likely voter screens applied at the end of the campaign nudged the horse race numbers in a more accurate (and more Republican) direction, why not apply such screens now?

The historical pattern of voter screens producing more Republican results remains as valid as ever. For example, when IPSOS pollster Chris Jackson used a likely voter screen to narrow April and May samples, he found that a 7 percentage point Obama lead over Romney among registered voters (42 to 35 percent) narrowed to just three points among the most likely to vote (46 to 43 percent).

Similarly, the Pew Research Center has reported that Republicans held a significant advantage throughout 2012 on measures of voter engagement. On its most recent survey, for example, Pew found that Romney supporters were more likely than Obama supporters to say they had given quite a lot of thought to the election (70 percent versus 62 percent).

So why not use these questions to create a full-blown likely voter screen for the most recent results?

These "measures of engagement and intention to vote are useful as indicators of likely turnout on the aggregate level" at this stage in the campaign," Pew Research associate research director Michael Dimock explained to The Huffington Post in June, "but they are only loosely predictors of whether an individual is or is not likely to vote this November."

"As we get closer to Election Day," he added, "particularly after the conventions and into the debate season -- these indicators become stronger."

Similarly, IPSOS' Jackson reports that its standard practice is to wait to report likely voter results until October. "We do this," they explain, "because people are notoriously poor predictors of their own likelihood of voting on Election Day." Likely voter models require "a number of assumptions," he argues, "and our belief is that we should wait to make those assumptions until a) as late in the process as possible and b) after important trends -- like voter enthusiasm -- become clearer."

But it's not just the media pollsters. David Winston, a Republican who advises U.S. House Speaker John Boehner, tells his clients to focus on numbers for registered voters. While the universe of registered voters includes virtually all of the potential electorate, Winston explains, a pollster who uses a likely voter screen "substitutes their judgement in defining a specific [turnout] scenario." A pollster "can play out some scenarios to just see what could happen," he says, "but to a large degree that just represents guessing."

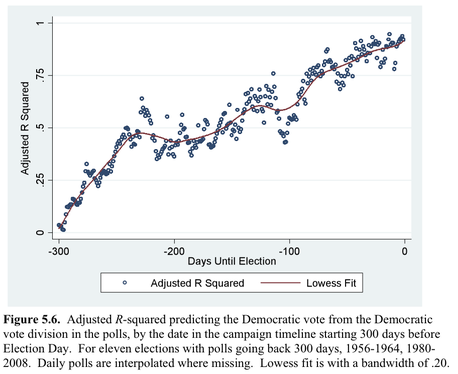

Another reason not to obsess over the relatively small differences between registered and likely voter samples is that polls taken before the party conventions remain imperfect predictors of the ultimate outcome. Political scientists Chris Wlezien and Bob Erikson have examined the issue for "The Timeline of Presidential Election Campaigns," their forthcoming book on election forecasting. A chart from their book (reproduced below with permission) shows that the predictive power of head-to-head polls will rise significantly after the party conventions, but remains more iffy now, more than 110 days before the election.

A look back at polling trends in recent elections explains why. In almost every election dating back to 1980, the margins separating the top candidates in horse race polls shifted significantly after the party conventions. Only in 1996 did those margins remain roughly the same throughout the year. In other years, the shifts in voter preferences that occurred after the party conventions, shifts that have benefited both Democratic and Republican candidates, would have overwhelmed the relatively modest differences that earlier likely voter screens would have produced.

In the end, if all pollsters applied likely voter screens right now, Romney's numbers would be slightly better, but there is a long way to go before any horse race poll should be considered an accurate forecast of the outcome.